On behalf of GWP China, Yunzhong JIANG, regional coordinator was invited by the ISC to jointly the editors group revealing critical water challenges alongwith corresponding science–policy–practice solutions.

The brief groups the numerous water challenges into four main categories with associated examples and focal areas that each demand different scientific responses. Together with concluding advice, this policy brief aims to efficiently engage with policy- and decision-makers and other stakeholders at UN- and Member States-level to translate scientific insights into tangible improvements and support the water-related Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the achievement of the 2030 Agenda.

Drawing on the expertise of its broad-based membership in the natural and social sciences as well as technology, the ISC is prepared to provide integrated, independent and evidence-based advisory support to UN-Water, to the relevant organizations of the UN system, and to Member States as needed to achieve SDG 6 and other relevant SDGs.

What are the key messages in the policy brief?

The world is not on track to meet global targets related to water as defined in SDG 6 and other relevant SDGs. Water crises across the globe threaten the achievement of key development and environmental goals and ultimately all the SDGs, given the centrality of water in social, political and economic affairs across all scales.

There are four categories of water challenges that require different science–policy–practice strategies to address them. These challenges range from well understood issues that only lack implementation of proven solutions to new and emerging issues that require additional research and innovative thinking. This brief describes such issues and opportunities to translate knowledge into solutions and improvements on the ground.

Science is indispensable for generating knowledge to address the complex interplay of natural and human factors that still hinder progress in resolving current water challenges. This requires a more systematic dialogue between policy-makers and scientists on evidence-based policy options to support tangible action and anticipate future water-related risks.

Category 1. Persistent water issues with known solutions

Amongst the issues identified under this category, the provision of piped water, of sanitation and hygiene facilities, and managing massive water losses from pressured urban reticulation systems, are some of the most telling examples of persistent water issues that have known solutions but lack implementation. The scientific focus needs to be on understanding socio-economic, cultural, and political factors that may hinder the implementation of best practices, assessing costs and benefits of interventions, and developing low-cost and locally appropriate solutions. Overall, addressing this category of issues requires better understanding, addressing barriers to implementation, and bridging the science to action gaps through transdisciplinary collaborations.

Category 2. Identical challenges requiring differentiated solutions

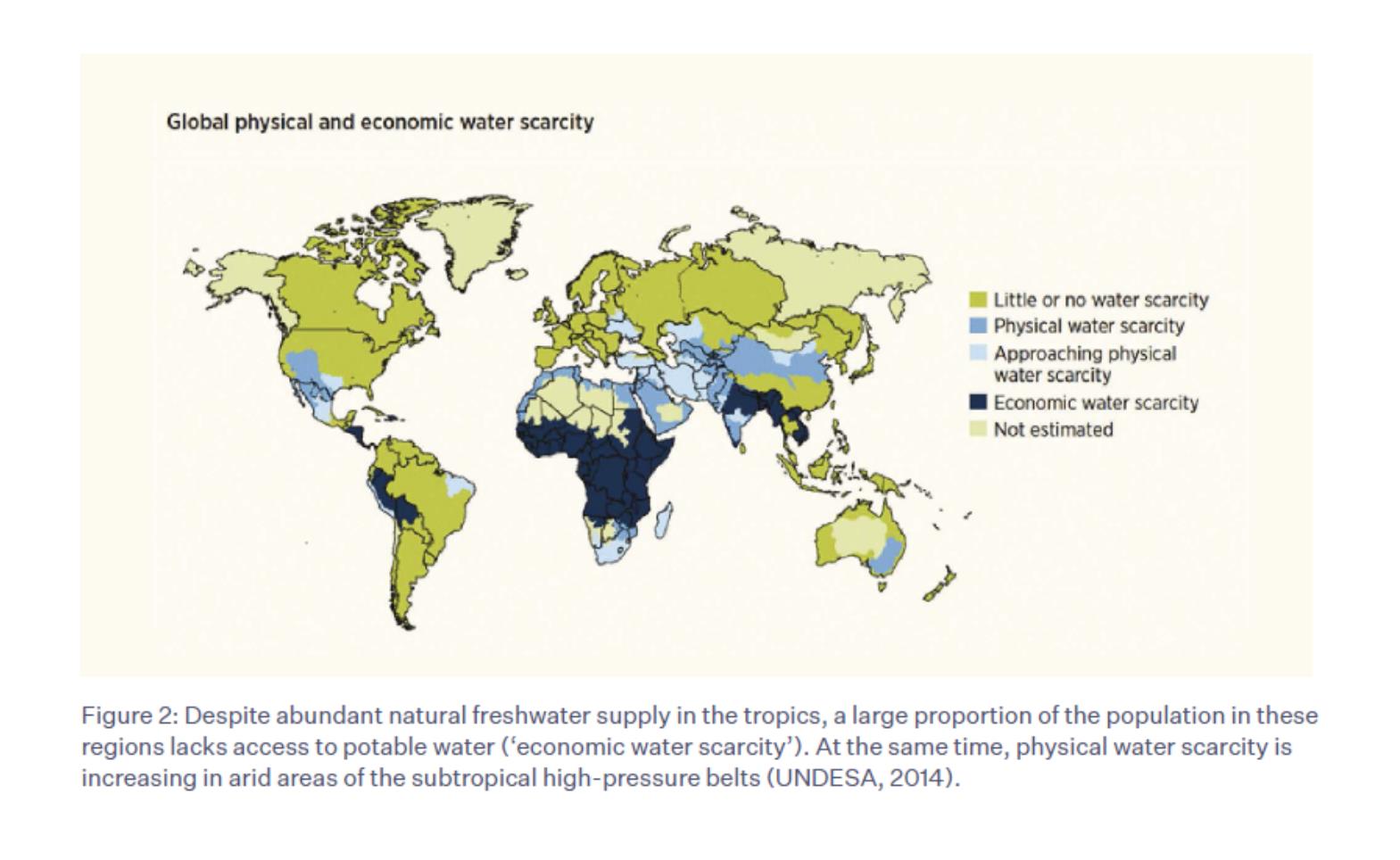

Some water challenges appear to be similar in nature across different parts of the world, however they often have different natural or socio-political causes requiring differentiated solutions. For example, for physical water scarcity, affluent countries tend to have advanced technological solutions, while low and middle-income countries often champion low-cost alternatives. Physical water scarcity is different from economic water scarcity, which in water-rich regions is due to poor infrastructure and insufficient funding. To address these challenges, scientific focus should be put on expanding social science-driven analysis, identifying applicable solutions, including drawing on indigenous and traditional knowledge, assessing the full range of anthropogenic impacts on water, and developing strategies for transferring and adapting tried-and-tested solutions to different local conditions. This requires collaboration between scientists, engineers, planners, stakeholders, and decision-makers to address water service provision and incentivise behavioural changes in water consumers, amongst others.

Category 3. Rapid changes requiring new solutions

Category 3 involves rapid changes related to environmental conditions such as weather and climate change, and socio-economic conditions such as global urbanization and demographic changes, that require new solutions. To address these challenges, focal areas for science to action include understanding and managing the impacts of urbanization on water resources, mapping and quantifying seawater intrusion and recharge rates of karst aquifers as drinking water source, and exploring perceptions and acceptability of reusing treated wastewater. It’s also important to enhance local accountability, ensure affordability and suitability of solutions for resource-restricted economies, and develop new approaches like sponge city concepts for urban runoff management and managed aquifer recharge.

Category 4. Addressing emerging and future water issues

Addressing emerging and future water issues requires considering the impacts of transitioning to a low-carbon society and zero-waste circular economy, and shifting interrelations within the water-food-energy-resources nexus. Science must concentrate on assessing the water implications of the green energy transition, improving forecasting and flood/drought warning systems, and developing solutions for the efficient removal of emerging contaminants from wastewater. Additionally, there is a focus on turning water from a source of conflict into an opportunity for cooperation and addressing security aspects related to water-related conflicts.

(Click the right column for reading the full report)