Summary

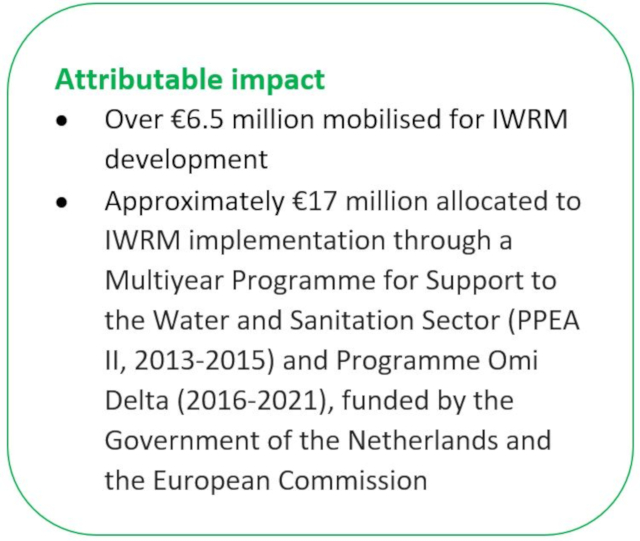

As part of the Benin government’s programme to develop an IWRM plan, it tasked GWP with mobilising stakeholders to define a vision and roadmap for improving water resources management. The IWRM plan’s development was facilitated by GWP Benin (the Country Water Partnership), with support from GWP technical and financial partners. This process led to the incorporation of IWRM principles in multiple national Strategies for Growth and Poverty Alleviation (SCRP), the government’s 2009 national water policy, and its 2010 national water law. A total of over €23 million was generated for the implementation of Phases 1 and 2 of the national IWRM action plan.

Background

The Benin’s commitment to IWRM dates back to the late 1990s, when a national water resources management study recommended an integrated approach. This recommendation sought to address fundamental weaknesses including:

- Fragmented strategy due to multiple decision-making centres, overlapping roles, and a lack of collaboration between stakeholders;

- Inadequate and unenforced legal frameworks;

- A lack of hydrological information;

- Scarce availability of management tools and decision support mechanisms;

- A chronic shortage of qualified human resources.

Benin formally committed to making the elaboration and implementation of a national IWRM action plan a priority in 1998 with the Kouhounou Declaration. It reconfirmed this commitment in 2002 at the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) by signing onto the international target for every nation to develop a national IWRM action plan.

As a result, IWRM principles were included in various national development planning frameworks, including multiple SCRPs (2003-2005, 2007-2009 and 2011-2015). Additionally, a Technical Permanent Secretariat for Coordination and Promotion of IWRM (STPC-GIRE) was established in 2004. Most importantly, a programme to develop a national IWRM action plan, supplemented by a portfolio of investment projects, was launched under Benin’s Ministry in charge of water, and facilitated by GWP’s Partnership for Africa’s Water Development (PAWD) programme. Phase 1 of the IWRM action plan was developed through multi-stakeholder engagement between 2005 and 2010.

GWP Contribution

The establishment of the Benin Country Water Partnership in 2001 laid the foundation for the development of a national IWRM action plan by pioneering capacity building initiatives that improved key stakeholders’ understanding of IWRM principles and implementation.

Benin’s government formally requested GWP’s support in developing its national IWRM action plan. GWP’s first task was to reignite sectoral ministries’ interest in IWRM, which had decreased due to a lack of tangible progress since the Kouhounou Declaration and the WSSD. GWP Benin’s proactive and persistent advocacy led to the establishment of a management committee to oversee the IWRM planning process. GWP Benin provided the committee’s Vice-Chairman and Deputy Secretary, thereby counter-balancing the political weight and maintaining impartiality. All stakeholders approved a IWRM roadmap structured according to the steps of the IWRM planning cycle developed by GWP under the PAWD programme.

As well as playing a key role in management mechanisms, GWP Benin mobilised its network to support a decentralised approach. Area Water Partnerships (AWPs) were established in 8 different regions. These AWPs facilitated local participation in the plan’s development, training sessions, and consultation workshops.

GWP was also responsible for engaging with media to maintain visibility of the process.

GWP Benin has retained a key role in supporting the implementation of the completed IWRM plan. This includes maintaining the neutral partnership platform established as an essential component of the plan and acting as an advisor to the plan’s Sterring Committee, which was set up to monitor progress and mobilize external financing.

Results

The key governance outcome from the IWRM planning process was the formal adoption of Benin’s national IWRM action plan.

The IWRM plan has three 5-year phases. Phase 1 (2011-2015) includes the definition and costs of priority actions as well as governance reforms identified as necessary for achieving plan objectives, such as establishing a Steering Committee, an Implementing Unit, and Basin and Local Committees. The total budget for Phase 1 was approximately €22.5 million.

Phase 2 (2016-2020) pushes for improved coordination of IWRM implementation at all watershed levels. The budget for Phase 2 is €36.8 million; external financing is estimated to represent 59%.

The IWRM planning process was successful in mobilising finances for sustainable water management. This dates to 2006 when the Government of the Netherlands set up PPEA I in Benin, which included over €5 million to support IWRM. An additional €1.6 million was secured from other partners, including the governments of Denmark, Germany, and France.

In terms of implementation, the Government of the Netherlands and the European Commission provided support in funding PPEA II (2013-2015) and Programme Omi Delta (2016-2021), which use Benin’s national IWRM plan as a reference document. Total funding for these programs is over €100 million; approximately €17 million is specifically allocated to IWRM interventions.

Benin began a IWRM deltaic planning process targeting the Ouémé basin under PPEA II. GWP Benin is working to improve understanding of delta management among key stakeholders, including non-state actors.

The influence on water governance frameworks spread far beyond the creation of a IWRM plan. From a development planning perspective, the IWRM planning process was closely linked and incorporated into Benin’s SCRPs, which serve as key national reference documents on the country’s socio-economic development as well as mechanisms to align external funding with national priorities. Additionally, from a political and legal perspective, the IWRM process enabled Benin to develop a new national water policy in 2009 and a new water law in 2010, which provide the institutional basis for improved water management strategies.

Photo: “Stilt Village on Lake Nokoué” by E. Lafforgue